My daughter Maya sleeps in my painting studio. In the evenings I kiss her goodnight though she is 21. Maybe mothers always do that. I pass my hand over her forehead like I have done since she was a small child. Her brow no longer needs to be unstitched though. Her forehead is smooth. She is at peace, or just tired.

When I peek into the room it is often still early; she is either lying in the dark or finishing a movie, laptop propped upon her bent knees, on top of the blankets. One of them is a Pepto-Bismol-pink uncovered comforter. I suggested putting a cover on it but she resisted – and I suspect it’s more than laziness. It’s a down comforter that I have had since my single days. I used it uncovered myself because I didn’t know yet about comforter covers, in my 20’s, sleeping alone after my married lover had left for the night. My mother died too soon in my life to give me advice about what kinds of sheets to get, let alone what kind of men to date. I didn’t even know about putting bleach in a wash until after I had my own children. It had felt luxurious, buying that comforter, cover or not. The other blanket is dense cotton, a flat pale blue. My then-husband and I had gotten it for one of our earlier beds. Maya doesn’t want a sheet either; she prefers to sleep directly under both of these artifacts.

Once upon a time there was a prince who wanted to marry a princess; but she would have to be a real princess. He travelled all over the world to find one, but nowhere could he get what he wanted. There were princesses enough, but it was difficult to find out whether they were real ones. There was always something about them that was not as it should be. So he came home again and again and was sad, for he would have liked very much to have a real princess.

The pull-out sofa she sleeps on is stiff, a cheap Ikea model, steel-gray, a pole running through the length. She keeps it open, untidied. It doesn’t pay for her to redo the couch every day since I am not working in the studio right now. She says she doesn’t feel the pole, but I think she is telling me a white lie. I believe she feels it, but doesn’t want me to think she is uncomfortable.

One evening a terrible storm came on; there was thunder and lightning, and the rain poured down in torrents. Suddenly a knocking was heard at the city gate, and the old king went to open it.

She has set herself up in my studio because she does not want to revisit her past by sleeping in her bedroom again; I sleep in her room. She does not want to sleep in her brother’s old room, either, for fear it would signal some kind of permanence, or normalcy. In his room, the chestnut platform bed sits bare except for a white mattress-cover, and her cat who snoozes on the satiny surface. From the outside, it is ridiculous that she doesn’t sleep there. She has no real memories in that bedroom. Three of the six dresser drawers are empty. Luna, her cat, is already warming the bed. But even that, she explained, would imply that she was settling back in, which I interpreted as meaning that she would not be the different, newly hatched creature she needs to be.

It was a princess standing out there in front of the gate. But, good gracious! what a sight the rain and the wind had made her look. The water ran down from her hair and clothes; it ran down into the toes of her shoes and out again at the heels. And yet she said that she was a real princess.

Sleeping in her bedroom would, she fears, mean she is still the girl who dwelled inside the four walls of her rape. She would be encircled, again, by the rape. Instead, she sleeps within the womb of my paintings. For now, she is neither the Maya of her earlier years nor a freshly revealed being. She waits within this multi-hued, slightly oily-smelling space, an in-between time. Paintings of every size lean against the walls surrounding her. At night, she peers over the edge of her laptop to the angles of honey-wood stretcher-bars that frame whatever she watches. She sleeps amidst work from the different times of my life as an artist; she sleeps within my past, next to visions whose original meanings are largely forgotten, or are irrelevant.

“Well, we’ll soon find that out,” thought the old queen. But she said nothing, went into the bed-room, took all the bedding off the bedstead, and laid a pea on the bottom; then she took twenty mattresses and laid them on the pea, and then twenty eider-down beds on top of the mattresses.

She also sleeps next to a triptych that still pulses with its violent story: a painting of a rape. They hang one next to the other just above the couch bed, not turned to the wall. When I go into the room at night, I see her face illuminated by the computer’s glow. And, in that technological twilight, those paintings. What is exposed during the day: the tangle of bedding and the rape paintings; a painting of bodies on a raft done when we were figuring out how to survive; a painting I did of my middle-aged belly – a drawing of my son as an enraged adolescent glued to the upper-right corner. Nights, the rambunctious images slumber, save the rape paintings, which catch the glow of streetlights long after her laptop has been shut.

On this the princess had to lie all night. In the morning she was asked how she had slept.

She sleeps by this shared history that will always, likely, remain crepuscular. I painted the rape triptych towards the end of the legal procedure following the charges she pressed against the rapist. The case now over, we are back home; she sleeps within my work like a fetus; she percolates not in my body but in my work, in the body of my work. She didn’t move back home; she moved into my work.

“Oh, very badly!” said she. “I have scarcely closed my eyes all night. Heaven only knows what was in the bed, but I was lying on something hard, so that I am black and blue all over my body. It’s horrible!”

There is a small glass-topped desk beneath two corner windows, just behind the side of the bed where she places her head. A pile of computer paper leans Pisa-like to the left of the rolling chair, another stack on top of the glass, another stuffed into the shelf underneath. They are all drafts of my recent memoir, about the rape from my – the mother’s – perspective. Maya sleeps next to all of it. Scattered pages blow off the most recent version when she opens the window before bed, littering the floor. White tiles speckled with type. She leaves them, the fanned paper making a half-halo seen from above, as she sleeps, waiting for either the full to arrive or the vanishing of the half.

Now they knew that she was a real princess because she had felt the pea right through the twenty mattresses and the twenty eider-down beds.

Maya graduated from college last May, after finding out that she lost the case. Her valises line the wall where I normally prop my paintings while working. Clothing drapes across suitcases and boxes. One splayed heap is a collaged dirty-laundry mix of jeans, a blue striped sleep-shirt, beige linen pants, a teal turtleneck. Against the wall behind that jumble is a roll of paper on which I began a drawing. It also waits. I called this work an “infinite drawing” two springs ago, when I began it, implying that I would work on it forever – that it would never be done. They are both incubating, Maya and the drawing. Last week one of her new white t-shirts got charcoal on it that doesn’t seem to wash out. There’s always something on the floor that stains clothing. It is all infinite in this room, which is maybe the real reason Maya has moved in. She is surrounded with the kind of love artists learn to gel into paintings. She can’t stay there forever, but she can borrow it, the room and the infinite looking, for a while. And I can wait until she’s ready to move out. The bed I use in her old room has a fairly new hybrid memory-foam mattress. It is the most comfortable bed in the apartment, and I have a sore back.

Nobody but a real princess could be as sensitive as that.

Initially, she had brought the standing mirror from her old room into the studio, and leaned it against the framed edge of a portrait of her brother. Whenever I noticed, I inched it away from the painting, but would find it there again after a few days. Last night it was back in her bedroom. She might be getting ready to leave. Or maybe she doesn’t need to see herself any more.

So the prince took her for his wife, for now he knew that he had a real princess; and the pea was put in the museum, where it may still be seen, if no one has stolen it.

Maya says she has never been happier than the time she has been sleeping in my studio. This time of her deepest sleep, after the end of the rape case. She doesn’t shut the shades, so the morning sun helps rouse her. It – the case – and she – remain preserved in amber light, until she wakes looking out over the supplies I use to make new worlds.

There. That is a true story.

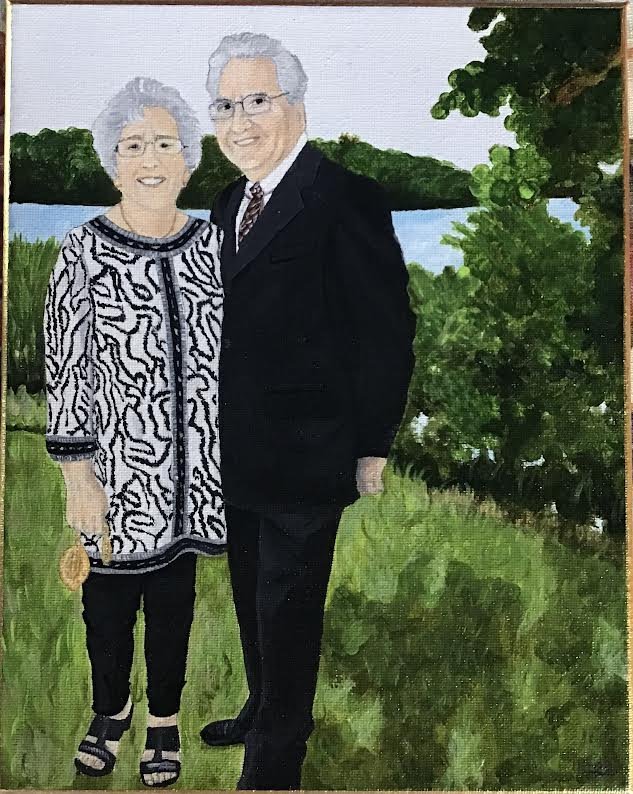

Karen Kaapcke

is an award-winning visual artist whose work is included in many private collections. She has exhibited broadly, both in the US and Europe. Notable awards include first–place for self-portrait at the Portrait Society of America, and finalist for the prestigious BP Portrait Award, where her painting was exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery, London. She recently completed a memoir about mothering her daughter through a rape, subsequent illnesses, a trial in France, and both of their recoveries. Karen maintains studios in New York City and France. More about her painting can be found at www.karenkaapcke.weebly.com

G&E In Motion does not necessarily agree with the opinions of our guest bloggers. That would be boring and counterproductive. We have simply found the author’s thoughts to be interesting, intelligent, unique, insightful, and/or important. We may not agree on the words but we surely agree on their right to express them and proudly present this platform as a means to do so.