As an actor, director, instructor and mentor, I firmly believe that the professional actor must constantly be WORKING. Whether gainfully employed as an actor or continually and diligently engaged in the study of your craft.

My ultimate focus in teaching is Scene Study. I am resolute that professional actors must be constantly engaged in preparing, building and creating characters in class. It is critical work, vital for satisfactorily attaining excellence in the actor’s art and craft. Whether you are working a paid acting job, or investing in your career by attending class, you must always be studying and plying your art and craft. This is the journey, the arc, and the ultimate objective of an acting career. Always be studying, preparing, self-educating, researching, practicing, and performing. This makes for more cultured and civilized artists, without whom, the world has significantly less humanity.

As a preliminary note, when I teach, my class focuses on scenes from theatre plays. Scenes are chosen by the actors from the entire historical canon of the world’s plays, from the Ancient Greek to the World Theatre of today and every period in between. Scenes from stage plays are most useful for instruction. We do not perform our scene work from screenplays, teleplays, novels or short stories. The primary reason for this is that the literature of the theatre is written specifically for the immediate live, emotional, spiritual and energetic exchange between actor and audience. There is no experience quite like it. Screenplays, teleplays, novels or short stories are created with the hope of that exchange to take place at a later time. Film and Television are more of a visual medium, produced with intention for that same exchange happening through the screen, albeit in a delayed fashion. Novels and short stories leave this exchange to the private imagination of the reader.

Throughout time, theater has played an important role in societies all around the world. The theater helped societies develop their religions and myths and played a key role in influencing thought throughout recorded history. Acting on the stage, doing the literature from the historical cannon is the focus of what I teach. It helps students learn to read and think critically. This training translates to professional acting in Feature Films and Television as well.

Scene Study is, as the name clearly implies, the study of scenes. It requires the preparation of a scene or segment of a play, performed with scene partners in front of the teaching director who will then give notes, directions, adjustments and suggestions to improve and advance the acting work along. Scene study is a vital practice for the professional actor. Like a good physical trainer, sports coach, or orchestral conductor, an insightful teaching director can avail much to the growth, experience and cohesion of the actor and their performances.

Scene study is the best environment to teach acting for the professional. With their partners they perform a dramatic or comedic scene and are then offered input, direction and feedback from teachers, classmates, and each other. Scene Study also allows the actor to learn how to prepare for performance by working out actions, objectives, blocking, and direction on their own before bringing it into acting class. Once presented, it is up to the teacher to direct and guide the actors into a more realized, fulfilling and honest portrayal and presentation of the playwrights’ work. This is how the actor grows, matures and keeps the total instrument sharp. With the energy of mind, body, soul, imagination, emotions and memory, our goal is to get all senses firing on all cylinders.

The greatest actors, the very best professional performers I have ever known NEVER STOP WORKING. If they are working on an acting gig for pay, they are working professionals. If they are paying to work on their craft in class, they are working professionals. Both reap rewards artistically and financially. This is the best way to invest in your acting career. The dividends are real and valuable.

Scene study hones skills such as emotional connection and character development as well as objective, tactics, and action. These are some of the intangible things that are not readily available to the actor working alone in a vacuum.

Scene Study class for professional working actors is best for the actors who already have a basic theatre education, training and technique and are ready to take their art and craft to a higher performance level that mirrors a paid work environment. It provides the discipline and focus required for the paid professional performances you do in your working career. Scene study class also allows the teacher to direct the actors so that they are very comfortable in the give and take of direction and in the collaborative artistic work environment.

Scene study compels the actor to listen, react, and focus on scene partners, take and receive notes, make adjustments and implement direction. This is important because it allows an actor to see if all the techniques and exercises they use in class can be utilized to create an honest and dynamic performance with their scene partner and director. It compels us to focus on the other actor and listen actively. Acting is REACTING. If the actor fails to listen and react the viability and believability of the scene vaporizes.

As to the networking and collaborative nature of our careers, one of my constant mantras is: “Work begets work, work begets friends and friends beget work.” This is a tangible benefit of Scene Study class.

Unlike the painter and his canvas, the musician and her violin, the dancer at the ballet barre, or even the woodworker and his lathe, the actor cannot exclusively work alone, without collaboration. Naturally, you can work your monologues, memorize and rehearse lines alone, but ultimately acting is a collaborative art. It requires an exchange of thoughts, words, energy, ideas and action between two or more souls. Other than being engaged in a paid acting job, most of our work as actors must be done in the constant pursuit of bettering and honing all of the necessary tools of the trade. The best place for that is in a solid and ongoing Scene Study Class with other professional actors and a strong teaching director. Truth be told, much of the professional work I have gotten in my entertainment career has come from friends and colleagues I’ve met on jobs and in acting classes. Those bookings far outweigh the auditions I have received from my agents over the years. Work, friends, networking, and acting class have all helped me book many, many lucrative acting jobs.

Let’s look at some simple definitions from the Oxford Dictionary.

· TECHNIQUE: A way of carrying out a particular task, especially the execution or performance of an artistic work. Acting is a Technique.

· METHOD: A particular form of procedure for accomplishing or approaching something. Acting is a Method.

· ART: The expression or application of human creative skill and imagination producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power. Acting is Art.

· CRAFT: An occupation or trade requiring skill as an artist. Acting is a craft.

· GIFT: A notable capacity, talent or endowment. Acting is a gift.

The results are interesting and have a common theme. Each definition above was the first result of researching each word. The importance of this bears further investigation and focus.

Being an actor requires acquiring and applying a wide range of skills encompassing the following:

TECHNIQUE: Good stage, screen or vocal presence.

METHOD: The ability to enter into another character and engage an audience.

MEMORY: The ability to memorize lines, movement, moments, memories.

INTELLECT: Good understanding of dramatic techniques.

INSPIRATION: Having the confidence, energy and dedication to perform.

IMAGINATION: Creative insight.

I am often posed with the question, “What is the difference between ‘Method Acting’ and ‘Classical/Technical ’ acting practices?” To which do I adhere to and teach? I always answer: why limit yourself to one style or discipline? Both are required to serve and inform the actor’s performance. Let’s briefly define each of these disciplines as both approaches to acting can be vital tools in the actor's quest for a truly believable performance.

Very simply put, “Method Acting” as we know it today began with Constantin Stanislavski at the Moscow Arts Theatre, which he co-founded in 1898 and developed until his death in 1938. Stanislavski method acting techniques, originally known as “The System” were developed to help actors build believable characters. The process, which allows actors to use their personal histories to express authentic emotion and create rich characters, has been taught by many great teachers since, including Stella Adler, Lee Strasberg and Sanford Meisner among others. It has matured and evolved over the ensuing years and has been the basis for many of history’s greatest performances. Method acting helps actors create believable emotions and actions in the characters they portray.

But even Stanislavski believed in and taught Classical Training or “Technique” as it is referred to today; it was necessary as a foundation to successful and memorable acting performances. He believed that the actor must possess in-depth knowledge of different classical techniques and principles through which they can improve their acting. Therefore, why try to separate the physical from the emotional experience in your practice and performance?

Technique or Classical Acting has been around for centuries, although it has its modern roots in the British theater. More focused on control and precision in performance, classical actors are more action-oriented rather than emotion-oriented. Classical actors often bring their characters to life with exactness and meticulousness and the solid delivery of a well-written scene can make a deep and memorable impact on audiences all the same.

Classical acting is a very broad term that takes into consideration the foundations of training and skills the actor acquires through study and practice. This includes: voice production, movement, speech, and practicing those skills while working on classical as well as modern plays. A classically trained actor also knows how to handle verse and understands the classics from the Greeks to Shakespeare, to the modern drama of today. Quite simply, Classical Acting suggests that the actor has spent a considerable amount of time in Classical Training. These are very brief definitions of the acting philosophies I believe in and teach.

It is my firm belief that actors must bring together both method and technique into their art and craft. You must have a deep working knowledge and expertise in both method acting and technical acting so that you have a smooth blend of both. A careful, calibrated and deft blending of both acting philosophies, results in a more satisfying and fulfilling “Method/Technique.” Either discipline practiced to the exclusion of the other has less gratifying results, in many cases for both the performer and the audience. So, is acting an art or a craft? I say the two are most definitely inextricable. As the years go by, with constant work, your gift set coupled with craftsmanship can result in an ownership of your art, in other words: mastery.

The painter, the potter, the musician, the dancer and the actor must all have a solid foundation, grasp and proficiency with their technique or craft, before they can truly be free to create art. If the painter doesn’t know the brushes, canvases and paints thoroughly it restrains their freedom and ultimately their art. Also, the painter must have knowledge of art history, individual artists, the masters, the canon of world art, art methodology, and art theory as they all inform artists in their individual art and in their individual creative moments.

As an Actor, getting yourself a broad education in basic acting technique, stagecraft, scenic design, lighting design, costuming, makeup, stage direction, stage management, theatre history, drama, comedy, the classics, and Shakespeare are all critical building blocks. Having this overarching knowledge of the theatre allows all of that study to be in you, part of you, and readily available to you. It informs your performances consciously and subconsciously. It brings comfort, peace and relaxation to your creative being. In this case knowledge truly IS power. Then and only then can you be the complete artist to freely prepare, build, and create living characters, roles, and performances.

By definition, the word craft refers to a set of skills that with sustained learning and practice over time leads to high levels of proficiency. Gaining a craft is a commitment. For some, it is a lifelong journey. For the very best work, it is required. Actors are tradesmen and acting is, as a vocation, the plying of your craftsmanship in an artistic way. This takes practice, technique, skill and a certain gift set. Mastering it takes a lifetime.

What is being gifted? For starters, it is a blessing. However it is just the beginning of art. Your gift set is the starting point and without diligent application it can be squandered. Instinct, imagination, intellect, vision, a sharp mind, a good instrument, and inspiration… these are all gifts. Happy are those who have multiple gifts, but that is simply the beginning. The actor must blend their gift set with focused, continual practice of the art and craft of acting. That is the work. A. B. C. = Always Be Creating!

Acting as your ART requires Action, Imagination, Concentration, Relaxation, Emotion, Memory, Motivation, a Sense of Truth and Faith and ultimately, Communion with others. Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration, and recognizing that is where true genius lies. Applying that knowledge is the key to success. The Actor must relentlessly pursue THE WORK. This all adds up to real moments of living the scene and the character in unison with your fellow actors. It allows your body, mind, emotions, and soul to remain loose while your art, craft, technique, and performances remain tight. You have to stay loose to be tight. Artistic flow comes from this work and its discipline. Artistry comes from a solid classical foundation with incessant study and practice.

The premise and philosophy of what I teach in my professional scene study class, entitled “THE WORK” is very direct, very straightforward and very simple. Actors MUST always be working, whether you are being paid to work, or paying to do your work. Every professional actor knows there will always be times between paying acting jobs. It is vital to always be practicing your art and craft, even between those paying jobs. Like a doctor practices medicine and a lawyer practices law, so too must professional actors practice their art and craft thus rendering a career as viable as medicine or law, and for a select few just as lucrative. The continual and constant scene study we practice in class ensures the professional actor is persistently and diligently studying, working and growing, honing, and sharpening their tools. Our art demands it of us and that’s exactly what scene study class is for and why it is so vitally imperative.

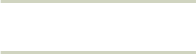

Christopher “Chiz” Chisholm is a classically trained, award-winning Actor, Director, Producer, Writer, Creative Executive and acting teacher who has spent his career in all facets of the entertainment industry. As an actor he has appeared on the New York stage and Hollywood soundstages, as well as repertory and regional theatres across the country and around the globe. Mr. Chisholm has performed in over 200 stage productions, feature films and television shows in his rich career. From Shakespeare to Shepard and Albee to Williams, Chiz has starred in classics, comedies, dramas and dozens of musicals over the years. Chiz has been teaching Acting, Technique, Scene Study, Audition Preparation and The Business of Show Business for over 30 years from coast to coast and around the globe. From New York to Los Angeles, Miami and Texas to Minneapolis, Chiz has worked with professional adult actors to assist in the honing of their craft, navigating their acting career paths and helping them to book jobs. Chisholm currently runs an ongoing scene study studio called THE WORK.

G&E In Motion does not necessarily agree with the opinions of our guest bloggers. That would be boring and counterproductive. We have simply found the author’s thoughts to be interesting, intelligent, unique, insightful, and/or important. We may not agree on the words but we surely agree on their right to express them and proudly present this platform as a means to do so.